Andelka M. Phillips*

At the opening of the Senate Committee on the Judiciary hearing which commenced on 11 June 2025 [1] Senator Chuck Grassley, Chairman of the Committee stated:

“Genetic data is the blueprint to a person. It is sensitive, it is personal and in the wrong hands, it is dangerous.” He went on to say that “Data is a weapon, and genetic data is a particularly potent weapon.”[2]

Introduction

Our personal data is everywhere online. From online dating to buying your groceries, our lives are increasingly being made public. Our lives are in a sense performed publicly whether we are aware of this or not. As well as sharing data both publicly and privately, we often share our most sensitive data with companies marketing new services. This is particularly common in the context of the HealthTech space. A prime example of this is direct-to-consumer genetic testing (aka DTC or personal genomics) which has created a market for DNA tests in the consumer space. It has done this sitting outside traditional governance frameworks that apply to DNA tests conducted in a clinical setting. This does involve an element of trust. We trust that these businesses will protect our most sensitive data, but is this trust misplaced? My answer to this question is yes.

But just where is all this data going? How is it being used and what happens when something goes wrong? And this final question is a matter of when, rather than if, as no business can guarantee security of information and so many industries are experiencing large data breaches.

As well as using popular wearable tech to track many different aspects of health and wellness, or taking online fitness classes, specific industries have developed centred around particular types of sensitive data. The consumer genomics industry relies on harvesting consumers’ genetic data together with troves of other forms of their personal data. As I have previously written, this industry has remained largely self-regulated and the main means of industry governance has been the contracts and privacy policies of DTC companies.[3] The contracts can, in fact, be seen as a form of private legislation imposed on consumers.[4] As is mentioned in the Senate Committee on the Judiciary hearing, which is referenced further later in this piece, the reality for most consumers is that they fail to read or even notice both contracts and privacy policies in the online world. In 2016, the Norwegian Consumer Council estimated that the average smartphone contained 250,000 words of terms and conditions.[5] In another example, CHOICE in Australia found that it would take 9 hours just to read Kindle’s terms and conditions.[6] More recently, in 2023, Nord Security estimated that it would take “46.6 hours … to read the privacy policies of the 96 websites Americans typically visit monthly.”[7] Unfortunately, even where consumers do choose to read contracts and policies, it is likely that they may face challenges in understanding the meaning of the terms contained in these documents. Becher and Benoliel’s study of the readability of the 500 most popular US website terms and conditions found that most of these contracts were written at the same level as academic journal articles and would generally require “more than 14 years of education” to understand.[8] And in my work with Becher, we found that it was possible to get through to the payment screen on several DTC websites, without ever viewing the contract or privacy policy.[9]

This piece is linked to two previous blog posts for this series: In safe hands? The protection of privacy in consumer genomics; and Hacking your DNA? Some things to consider before buying a DNA test online. In this follow up, I consider recent developments related to 23andMe’s bankruptcy proceedings and impending sale of the company. Previously, the winning bidder on the company was pharma giant Regeneron[10] and the backup bidder[11] TTAM Research Institute. TTAM is a nonprofit medical research organisation founded by 23andMe’s former CEO and co-founder Anne Wojcicki.[12] More recently, in a second auction, TTAM has won the auction for $305 million US dollars, with the company announcing “that it has entered into a definitive agreement with former CEO Anne Wojcicki’s TTAM Research Institute for the sale of substantially all the company’s assets…”[13] This new agreement includes provision that TTAM will abide by the company’s existing privacy policies and allow for account deletion. However, the previous history of the company, including its data breach, the subsequent class actions, the Bankruptcy proceedings, and the US Senate Committee on the Judiciary hearing which commenced in the last week (mentioned further below[14]), together with the lawsuit brought by 27 state attorneys-general and the District of Columbia,[15] means that many things for 23andMe and their consumers are in a state of flux. The sale to TTAM will still require approval from the Bankruptcy Court, and the hearing and lawsuit by the attorneys-general, and a newly proposed Bill for the Don’t Sell My DNA Act[16] could impact this sale. I also believe that if the purchase goes ahead, consumers should still be concerned.

I wish to highlight why selling the company to pharma or another entity should not come as a surprise and make a renewed call for improved oversight of this industry. This is an industry which from its beginnings has had sharing and reuse of data at its heart, rather than a focus on protecting the security and privacy of consumers’ data. This sharing comes in many forms. It is not only about partnerships and mergers that a company might enter into, it is also about encouraging consumers to connect with unknown relatives and share other forms of data through a company’s platform. There is value in having a large database and it is not just the digital genetic data that has value, but also the physical samples of spit collected from consumers. More attention also needs to be paid to what is happening to physical samples of saliva that have been stored by the company. As proceedings in the US are ongoing, I am planning further work on this.

23andMe is a market leading DTC genetics company, possessing one of the largest consumer databases with approximately 15 million consumers’ data. Since its beginnings in 2006,[17] it has been one of the best-known companies in this space. A once unicorn company, valued at a market cap of more than $1 billion USD in 2015[18] and later being valued at $6 billion USD.[19] It has also had links with Big Tech since its inception. Its co-founder Anne Wojcicki and former CEO was formerly married to Sergei Brin who was the co-founder of Google and Google has invested in the company (with investments of $3.9 million USD in 2007 and $2.6 million USD in 2009).[20] Wojcicki resigned from her position as CEO in March 2025.[21] It should also be noted that Wojcicki’s sister is also the former CEO of YouTube.[22] This is also not the only player in the DTC space that Google has had links with. Another example is Google’s subsidiary Calico’s collaboration with AncestryDNA.[23] I plan to explore more of the competition law issues raised by this industry in future work.

The 23andMe data breach

The earlier blogs mentioned the massive data breach experienced by 23andMe in 2023, which has impacted almost half of its consumers – some 6.9 million people, including children, and the subsequent class actions that have followed this breach. Unfortunately, since the provisional approval of a $30 million (USD) settlement in December 2024, the situation has deteriorated further.[24] In March of 2025, the company filed for Chapter 11 Bankruptcy protection.[25] Then in May 2025, an agreement was reached to sell the company, including consumers’ data to Regeneron,[26] which is a leading pharmaceutical company. More recently in the second auction, the agreement 23andMe has reached with TTAM nullifies the earlier deal with Regeneron.[27] In the aftermath of the earlier data breach and the more recent news of the bankruptcy, many consumers have tried to delete their data, but there have been problems with doing this. This has led to the US House Committee on Energy and Commerce launching an investigation of how the bankruptcy will impact consumers’ data.[28] This has in turn led to a US Senate Committee on the Judiciary hearing commencing on 11th June 2025 – more on this below.

Key points to keep in mind:

Before continuing, there are four points that should be emphasized. Firstly, the breach that impacted 23andMe should not be viewed as limited to impacting the 6.9 million people whose data was compromised, but also their wider family group. This is because of the shared nature of DNA – it means that many more millions of people could be impacted over the longer term by this breach.

Secondly, while a settlement had been provisionally approved for the US class actions, it is now likely that consumers may not end up receiving any compensation from this settlement. Compensation at an individual level was always going to be limited under the terms of the settlement, but now the settlement itself has been put on hold and is being challenged by 23andMe’s lawyers.[29] This should further highlight the reality that victims of data breaches often are left in the cold with very limited options for redress and this is something that needs to change. While most peoples’ lives have moved increasingly online in the last two decades, the future risks that many services collecting our most sensitive data pose need to be taken more seriously.

Thirdly, a sale of 23andMe including its entire database will pose risks not only for all its 15 million consumers, but the millions of people whom they are related to.

Finally, it is common for the contracts and privacy policies to contain problematic clauses, which could be challengeable as unfair terms and raise questions about the validity of consent in the context of consumer genomics, but also other HealthTech industries. It is particularly common for companies to allow themselves broad power to change their terms. This is not unique to 23andMe, but common practice in this industry and it is an area in need of reform.

Recent developments in the USA

Now turning to recent developments, the future of 23andMe’s database and how its consumers’ data will be used is currently hanging in the balance. The company is based in the US and in light of the publicity around the breach and 23andMe’s financial problems, the US Senate and Congress are now taking an interest in 23andMe’s future. The Bankruptcy Court has also appointed a privacy ombudsman to 23andMe, who “will investigate and report to the court on the security program of the buyer, the potential costs and benefits of the sale to customers, and whether the sale is consistent with 23andMe’s privacy policies and applicable laws.”[30]

This was followed by a number of very recent developments. On the 9th of June attorneys-general from 27 US States together with the District of Columbia sued the company in order to prevent the sale of their States’ consumers’ data without consumers’ consent.[31] This is a bipartisan initiative. Then on 10th June 2025, the US House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform held a hearing entitled ‘Securing Americans’ Genetic Information: Privacy and National Security Concerns Surrounding 23andMe’s Bankruptcy Sale’.[32]

Subsequently, on the 11th June of 2025, a US Senate Committee on the Judiciary hearing entitled ‘23 and You: The Privacy and National Security Implications of the 23andMe Bankruptcy’ began.[33] In these proceedings, concerns have been raised by a range of people from different sides of the political spectrum with testimony from Professor I Glenn Cohen and Professor Brook Gotberg.

Senator and Ranking Member Richard Durbin expressed his concerns about future uses of consumers’ data not being in line with its current policies to Joseph Selsavage (the Interim Chief Executive Officer and Chief Financial and Accounting Officer of 23andMe), in these words:

“2 or 3 buyers removed – your best intentions don’t mean much”

and that “unless we had a federal law relative to this issue that applies to future transactions your best intentions don’t mean much.”[34]

Senator Durbin also mentioned the example of the HeLa cell line developed because of samples of a tumour from Henrietta Lacks and emphasized the lack of consent or compensation provided to her and her family and made this comment:

“Part of what’s being sold by 23andMe is a collection of biological samples submitted by consumers who wanted their DNA examined. They may have consented to some use of those samples, but I question how informed it actually was. And there’s no guarantee a new owner won’t change how those samples are used…”[35]

In response to this, Professor Cohen in his testimony also emphasized that 23andMe has not explained why they are not recontacting their consumers to provide consent to the transfer of their data, asking “why aren’t they doing it?”[36]

Senator Josh Hawley also raised concerns about 23andMe’s Privacy Policy referencing specific sections of the policy. It was noted that the Policy indicates that data can be retained by the company even after a consumer has asked for it to be deleted. This is not surprising. This is in line with my own research on the industry’s contractual terms over the last decade. In my review of 71 companies’ contracts, I found it very common for companies to leave themselves broad power to change terms, often without notice.[37] Furthermore, 23andMe’s policies have for years allowed sharing data with affiliates, which could include all their previous partners.[38]

A point to remember here is that while the concerns raised in the USA can be seen as positive steps for widening the debate about the protection of privacy in relation to genetic data specifically and sensitive data more generally, this is not a matter that only impacts American consumers. 23andMe has sold its tests internationally and there are privacy risks for its international consumers on a global scale. It should also be understood that even though it appears the majority of 23andMe’s customers are American this should not encourage complacency, as many Americans have close relatives in other countries. Likewise, if 23andMe’s bankruptcy and data breach raises national security concerns for Americans, it also raises national security concerns for citizens of other nations.

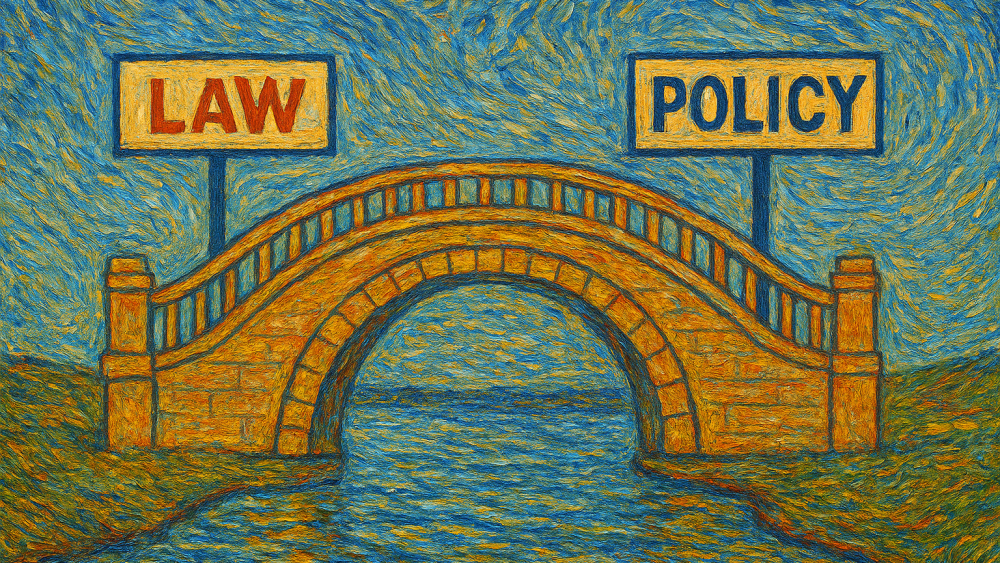

One further development, which could lead to positive regulatory reform in the USA, is a new bipartisan Bill for a Don’t Sell My DNA Act.[39] This legislation, if enacted, would reform the US Bankruptcy Code. It would improve protection for consumers’ privacy in the USA in three main ways:[40]

- “Modernizing the Bankruptcy Code to include genetic information in the definition of “personally identifiable information”;

- Requiring written notice and affirmative consumer consent prior to the use, sale or lease of genetic information during bankruptcy proceedings; and

- Requiring the trustee or debtor in possession of genetic information to permanently delete any data not subject to a sale or lease.”

I have previously suggested the need for industry specific legislation and I believe other amendments to existing law are necessary, but this Bill could lead to reform at least in the context of businesses that do have financial difficulties and face the prospect of being sold on. Given that much of this industry is based in the USA as well, there is a vital need for real reform in the USA.

Conclusion

Now is the time for reform! As has been mentioned in the ‘23 and You’ hearing genetic information can be used for a wide range of purposes, which may be against the interests of consumers. This is of course an area of future risk, but some of this unidentified future risk has already become a reality for some of 23andMe’s customers, who have been victims of identity theft or had their health information compromised. Other potential risks which were highlighted in the hearing are the ability to track and locate individuals and their relatives and the potential to use data to train AI models. Such uses are not far fetched. The use of Generative AI is expanding in all fields and there is growing interest in Generative Biology projects together with legitimate concerns about its risks.[41] Consumers need and deserve better protection.

I have previously written about the need for improved regulation of this industry both independently and jointly with others[42]. I am hopeful that these proceedings and the Bill will lead to some substantive reforms, but this is very much a case of too little, too late. We need new legislation in the US to regulate the industry and we need existing regulators to contribute to reform in this area. We need international collaboration to improve industry standards and specifically to improve cyber security practices in relation to genetic data and other forms of sensitive data more generally.

Mandatory codes of conduct, as well as user friendly model privacy policies and contracts for the industry would also be beneficial. Model privacy policies and contracts could be developed by existing regulators (both in the consumer protection and data protection spheres) which limit the ways that data can be used and allow consumers more control over their most sensitive data. In the US, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) could contribute to reform and the scope of legislation such as the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) could be expanded. I do believe that specific legislation applicable to all forms of consumer genomics would be beneficial though, as at present ancestry testing and other so-called ‘recreational’ testing often sits outside existing legislation.

Particularly problematic clauses that have been deemed unfair in jurisdictions including the European Union, the United Kingdom, New Zealand and Australia, should not be included in contracts targeting consumers in those jurisdictions. Furthermore, such clauses should be removed from American consumer contracts if we are to improve the protection of consumers’ rights in this context. Enhancing consumers’ rights to their data in this context, such as with a consumer data right would also be welcome, but it is vital that we move towards allowing consumers opportunities to understand risks and benefits in this context and the ability to make informed choices. We need companies to be held accountable, so that consumers are not left without recourse when a data breach occurs. I will end with a final point. While medical research has brought us many benefits, it, like technology itself is not neutral. Finally, not all research ventures will be beneficial to our most vulnerable communities, who have in fact often been exploited with no recompense.

As this article goes live, the news has also broken that the UK’s Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO) has announced that it is fining 23andMe “£2.31 million for failing to implement appropriate security measures to protect the personal information of UK users” in the attack it experienced in 2023, which led to the data breach.[43] This follows a joint probe by the ICO and the Canadian Office of the Privacy Commissioner (OPC). In the News statement they have released, the ICO states that “23andMe revealed serious security failings at the time of the 2023 data breach.”[44] This lends support to the need for reform of security infrastructure and practices throughout the industry.

Furthermore, according to the ICO, the breach has impacted “155,592 UK residents, potentially revealing names, birth years, self-reported city or postcode-level location, profile images, race, ethnicity, family trees and health reports.” Again, as previously noted the number of people impacted is likely to substantially exceed this figure, given that this information can link to a larger number of family members. The ICO highlights that the impacts on consumers could include surveillance, discrimination or financial loss and that they “received 12 complaints from consumers”.[45] I plan to write further about this together with the US developments, but am adding this here for the benefit of readers to keep this as current as possible.

* Dr Andelka M. Phillips is an Academic Affiliate, Centre for Health, Law and Emerging Technologies (HeLEX), University of Oxford and Affiliate with the Bioethics Institute Ghent (BIG), Ghent University. https://www.andelkamphillips.com, https://www.law.ox.ac.uk/people/andelka-phillips, https://www.bioethics.ugent.be/our-people/andelkamphillips/

[1] US Senate Committee on the Judiciary, ‘23 and You: The Privacy and National Security Implications of the 23andMe Bankruptcy’ – full committee hearing recording available here https://www.judiciary.senate.gov/committee-activity/hearings/23-and-you-the-privacy-and-national-security-implications-of-the-23andme-bankruptcy.

[2] US Senate Committee on the Judiciary, ‘Grassley Opens Judiciary Hearing on the Privacy and National Security Implications of 23andMe Bankruptcy’ Prepared Opening Statement by Senator Chuck Grassley of Iowa, Chairman, Senate Judiciary Committee, ‘23 and You: The Privacy and National Security Implications of the 23andMe Bankruptcy’ (11 June, 2025) https://www.judiciary.senate.gov/press/rep/releases/grassley-opens-judiciary-hearing-on-the-privacy-and-national-security-implications-of-23andme-bankruptcy.

[3] AM Phillips, Buying Your Self on the Internet: Wrap Contracts and Personal Genomics (Edinburgh University Press 2019); AM Phillips, ‘Reading the Fine Print When Buying Your Genetic Self Online: Direct-to-Consumer Genetic Testing Terms and Conditions’ (2017) New Genetics and Society 36(3) 273-295. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14636778.2017.1352468; AM Phillips, ‘Only a Click Away – DTC Genetics for Ancestry, Health, Love… and More: A View of the Business and Regulatory Landscape’ (2016) 8 Applied & Translational Genomics 16-22; and SI Becher and AM Phillips, ‘Data Rights and Consumer Contracts: The Case of Personal Genomic Services’ in D Clifford, KH Lau, JM Paterson (eds), Data Rights and Private Law (Hart Publishing, 14 December 2023). Earlier draft available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4180967; and forthcoming AM Phillips, ‘Owning me, owning you – How private companies acquire rights in our most intimate data’ in for G Reynolds, A Mogyoros, and T Dagne (eds),Intellectual Property Futures – Exploring the Global Landscape of IP Law and Policy (University of Ottawa Press 2025).

[4] AM Phillips, Buying Your Self on the Internet: Wrap Contracts and Personal Genomics (Edinburgh University Press 2019) p28.

[5] Norwegian Consumer Council, ‘250,000 words of app terms and conditions’ (24 May 2016) https://www.forbrukerradet.no/side/250000-words-of-app-terms-and-conditions/; and see the AppFail campaign page https://www.forbrukerradet.no/appfail-en/.

[6] Consumers’ Federation of Australia, ‘Nine Hours of Conditions Apply *’ (16 March 2017) https://consumersfederation.org.au/nine-hours-of-conditions-apply/.

[7] Nord Security, ‘Reading the privacy policies they encounter monthly would take almost 47 hours’ (13 December 2023) https://nordsecurity.com/press-area/research-americans-would-waste-a-whole-workweek-every-month-if-they-were-to-read-privacy-policies – this is referenced in the Senate Committee on the Judiciary hearing.

[8] S Becher, ‘Research shows most online consumer contracts are incomprehensible, but still legally binding’ The Conversation (4 February 2019) https://theconversation.com/research-shows-most-online-consumer-contracts-are-incomprehensible-but-still-legally-binding-110793; and U Benoliel and SI Becher, ‘The Duty to Read the Unreadable’ (January 11, 2019) 60 Boston College Law Review 2255 (2019), Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3313837 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3313837.

[9] SI Becher and AM Phillips, ‘Data Rights and Consumer Contracts: The Case of Personal Genomic Services’ in D Clifford, KH Lau, JM Paterson (eds), Data Rights and Private Law (Hart Publishing, 14 December 2023).

[10] Regeneron https://www.regeneron.com/ ; M Liebergall, ‘Pharma co. buys 23andMe and its DNA vault for $256 million’ Morning Brew (20 May 2025) https://www.morningbrew.com/stories/2025/05/20/pharma-co-buys-23andme-for-256-million ; R Winkler, ‘23andMe’s Fall From $6 Billion to Nearly $0’ The Wall Street Journal (31 January 2024). https://www.wsj.com/health/healthcare/23andme-anne-wojcicki-healthcare-stock-913468f4.

[11] Rylee Kirk, ‘23andMe Customers Did Not Expect Their DNA Data Would Be Sold, Lawsuit Claims’ The New York Times (10th June 2025) https://www.nytimes.com/2025/06/10/business/23andme-data-lawsuit.html#:~:text=The%20genetic%2Dtesting%20company%2C%20which,the%20data%20without%20express%20consent; NAAG Client States et al v. 23andMe Holding Co. et al, Case No. 25-04035, United States Bankruptcy Court for the Eastern District of Missouri, Eastern Division https://www.doj.state.or.us/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/Dkt-1-Complaint.pdf

[12] TTAM Research Institute https://ttamresearchinstitute.org/.

[13] Staff Reporter, ‘Wojcicki, TTAM Research Institute’s $305M Offer Wins Bidding for 23andMe in Second Auction’ GenomeWeb (13 June 2025) https://www.genomeweb.com/business-news/wojcicki-ttam-research-institutes-305m-offer-wins-bidding-23andme-second-auction.

[14] US Senate Committee on the Judiciary, ‘23 and You: The Privacy and National Security Implications of the 23andMe Bankruptcy’ – full committee hearing recording available here https://www.judiciary.senate.gov/committee-activity/hearings/23-and-you-the-privacy-and-national-security-implications-of-the-23andme-bankruptcy.

[15] Rylee Kirk, ‘23andMe Customers Did Not Expect Their DNA Data Would Be Sold, Lawsuit Claims’ The New York Times (10 June 2025) https://www.nytimes.com/2025/06/10/business/23andme-data-lawsuit.html#:~:text=The%20genetic%2Dtesting%20company%2C%20which,the%20data%20without%20express%20consent. ; Case 25-04035 https://www.doj.state.or.us/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/Dkt-1-Complaint.pdf ; and NAAG Client States et al v. 23andMe Holding Co. et 9 June 2025 al – https://www.pacermonitor.com/public/case/58476865/NAAG_Client_States_et_al_v_23andMe_Holding_Co_et_al

[16] US Senate Committee on the Judiciary, ‘Grassley, Cornyn Introduce Bipartisan Bill to Safeguard Consumers’ Genetic Data After 23andMe Bankruptcy Sparks Privacy Concerns’ (27 May 2025) https://www.judiciary.senate.gov/press/rep/releases/grassley-cornyn-introduce-bipartisan-bill-to-safeguard-consumers-genetic-data-after-23andme-bankruptcy-sparks-privacy-concerns; and see S.1916 – Don’t Sell My DNA Act, S.1916 — 119th Congress (2025-2026) https://www.congress.gov/bill/119th-congress/senate-bill/1916/text/is.

[17] 23andMe, ‘23andMe at 16’ (28 April 2022) https://blog.23andme.com/articles/23andme-turns-16

[18] AM Phillips, Buying Your Self on the Internet: Wrap Contracts and Personal Genomics (Edinburgh University Press 2019) p11 citing Aaron Krol, ‘What comes next for direct-to-consumer genetics?’ (Bio IT World, 2015) http://www.bio-itworld.com/2015/7/16/what-comes-next-direct-consumer-genetics.html

[19] Michael Levenson, ‘23andMe to Be Bought by Biotech Company for $256 Million’ The New York Times (19 May 2025) https://www.nytimes.com/2025/05/19/business/regeneron-pharmaceuticals-23andme-data.html

[20] BBC News, ‘Google invests in genetics firm’ (22 May 2007) http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/business/6682451.stm; Larry Dignan, ‘Google goes biotech, invests in 23andMe’ ZDNET (22 May 2007) https://www.zdnet.com/article/google-goes-biotech-invests-in-23andme/ ; FIERCE Biotech, ‘Google hands $2.6M to 23andMe’ FIERCE Biotech (19 June 2009) https://www.fiercebiotech.com/biotech/google-hands-2-6m-to-23andme

[21] See 23andMe Holding Co., et al. Case No. 25-40976-357, United States Bankruptcy Court for the Eastern District of Missouri, Eastern Division https://www.moeb.uscourts.gov/23andme-holding-co-information and also see https://www.pacermonitor.com/public/case/57373210/23andMe_Holding_Co; Ashley Capoot, ‘23andMe files for bankruptcy, Anne Wojcicki steps down as CEO’ CNBC (24 March 2025) https://www.cnbc.com/2025/03/24/23andme-files-for-bankruptcy-anne-wojcicki-steps-down-as-ceo.html

[22] Shiona McCallum, ‘YouTube CEO Susan Wojcicki steps down after nine years’ BBC (18 February 2023) https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-64675997

[23]AM Phillips, Buying Your Self on the Internet: Wrap Contracts and Personal Genomics (Edinburgh University Press 2019) p124, citing Erin Brodwin, ‘A collaboration between Google’s secretive life-extension spinoff and popular genetics company Ancestry has quietly ended’ Business Insider (1 August 2018) http://uk.businessinsider.com/google-calico-ancestry-dna-genetics-aging-partnershipended-2018-7?r=US&IR=T; GenomeWeb Staff Reporter, ‘AncestryDNA, Calico to Collaborate on Genetics of Human Longevity’ GenomeWeb (21 July 2015) https://www.genomeweb.com/business-news/ancestrydna-calico-collaborategenetics-human-longevity

[24] Alder, ‘23andMe Settles Data Breach Lawsuit for $30 Million’ The HIPAA Journal (16 September 2024) https://www.hipaajournal.com/23andme-class-action-data-breach-settlement/; A Bronstad, ‘Judge Approves 23andMe’s $30M Data Breach Settlement – With Conditions’ The Recorder (6 December 2024) https://www.law.com/therecorder/2024/12/06/judge-approves-23andmes-30m-data-breach-settlement—with-conditions/; and In re 23ANDME, Customer Data Sec. Breach Litig., 24-md-03098-EMC (N.D. Cal. Dec. 4, 2024) https://casetext.com/case/in-re-23andme-customer-data-sec-breach-litig-3/case-details.

[25] W Grantham-Philips, ‘23andMe files for Chapter 11 bankruptcy as co-founder and CEO Wojcicki resigns’ Associated Press (25 March 2025) https://apnews.com/article/23andme-chapter-11-bankruptcy-wojcicki-resigns-9827549d9171a537e76f60cb950d1823; A Zilber, ‘DNA testing pioneer 23andMe files for bankruptcy as concerns mount over data privacy of 15M customers’ The New York Post (24th March 2025) https://nypost.com/2025/03/24/business/dna-firm-23andme-files-for-bankruptcy/ ; and Attorney General Bonta, ‘Attorney General Bonta Urgently Issues Consumer Alert for 23andMe Customers’ (Press Release 21 March 2025) https://oag.ca.gov/news/press-releases/attorney-general-bonta-urgently-issues-consumer-alert-23andme-customers.

[26] Regeneron, ‘Regeneron Enters into Asset Purchase Agreement to Acquire 23andMe® for $256 Million; Plans to Maintain Consumer Genetics Business and Advance Shared Goals of Improving Human Health and Wellness’ (Press Release, 19 May 2025) https://newsroom.regeneron.com/news-releases/news-release-details/regeneron-enters-asset-purchase-agreement-acquire-23andmer-256.

[27] Staff Reporter, ‘Wojcicki, TTAM Research Institute’s $305M Offer Wins Bidding for 23andMe in Second Auction’ GenomeWeb (13 June 2025) https://www.genomeweb.com/business-news/wojcicki-ttam-research-institutes-305m-offer-wins-bidding-23andme-second-auction.

[28] Anthony Ha, ‘Congress has questions about 23andMe bankruptcy’ TechCrunch (19 April 2025) https://techcrunch.com/2025/04/19/congress-has-questions-about-23andme-bankruptcy/; see the letter from Representatives Brett Guthrie, Gus Bilirakis, and Gary Palmer to 23andMe https://d1dth6e84htgma.cloudfront.net/04_17_2025_E_and_C_Letter_to_23and_Me_5c8d4032a7.pdf.

[29] C Loizos, ‘23andMe customers notified of bankruptcy and potential claims — deadline to file is July 14’ TechCrunch (11 May 2025) https://techcrunch.com/2025/05/11/23andme-customers-notified-of-bankruptcy-and-potential-claims-deadline-to-file-is-july-14/ ; A Raine, ‘Rule 23 And ME: The Problem With Class Action Lawsuits’ NULJ (22 February 2023) https://www.thenulj.com/nuljforum/classaction.

[30] Christi Guerrini and Amy McGuire, ‘The 23andMe Bankruptcy: Privacy Considerations and a Call to Action (Part 2)’ The Petrie Flom Centre Bill of Health (7 May 2025) https://petrieflom.law.harvard.edu/2025/05/07/the-23andme-bankruptcy-privacy-considerations-and-a-call-to-action-part-2/; and Dietrich Knauth, ‘23andMe will have court-appointed overseer for genetic data in bankruptcy’ Reuters (1 May 2025) https://www.reuters.com/sustainability/boards-policy-regulation/23andme-will-have-court-appointed-overseer-genetic-data-bankruptcy-2025-04-29/.

[31] Rylee Kirk, ‘23andMe Customers Did Not Expect Their DNA Data Would Be Sold, Lawsuit Claims’ The New York Times (10 June 2025) https://www.nytimes.com/2025/06/10/business/23andme-data-lawsuit.html#:~:text=The%20genetic%2Dtesting%20company%2C%20which,the%20data%20without%20express%20consent; Case 25-04035 https://www.doj.state.or.us/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/Dkt-1-Complaint.pdf ; and NAAG Client States et al v. 23andMe Holding Co. et 9 June 2025 al – https://www.pacermonitor.com/public/case/58476865/NAAG_Client_States_et_al_v_23andMe_Holding_Co_et_al.

[32] House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform, ‘Securing Americans’ Genetic Information: Privacy and National Security Concerns Surrounding 23andMe’s Bankruptcy Sale’ (10th June 2025) – full committee hearing available here https://oversight.house.gov/hearing/securing-americans-genetic-information-privacy-and-national-security-concerns-surrounding-23andmes-bankruptcy-sale/ ; also see House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform, ‘Wrap Up: Congress Taking Action to Ensure the Safety of Americans’ Personal DNA Data’ (Press Release, 10 June 2025) https://oversight.house.gov/release/wrap-up-congress-taking-action-to-ensure-the-safety-of-americans-personal-dna-data/

[33] US Senate Committee on the Judiciary, ‘23 and You: The Privacy and National Security Implications of the 23andMe Bankruptcy’ – full committee hearing recording available here https://www.judiciary.senate.gov/committee-activity/hearings/23-and-you-the-privacy-and-national-security-implications-of-the-23andme-bankruptcy; and see Senator Chuck Grassley, ‘Grassley Opens Judiciary Hearing On The Privacy And National Security Implications Of 23andMe Bankruptcy’ (prepared opening statement, 11th June 2025) https://www.grassley.senate.gov/news/remarks/grassley-opens-judiciary-hearing-on-the-privacy-and-national-security-implications-of-23andme-bankruptcy.

[34] US Senate Committee on the Judiciary, ‘23 and You: The Privacy and National Security Implications of the 23andMe Bankruptcy’ – this is quoted from the video recording of the full committee hearing available here https://www.judiciary.senate.gov/committee-activity/hearings/23-and-you-the-privacy-and-national-security-implications-of-the-23andme-bankruptcy.

[35] US Senate Committee on the Judiciary, ‘23 and You: The Privacy and National Security Implications of the 23andMe Bankruptcy’ – this is quoted from the video recording of the full committee hearing available here https://www.judiciary.senate.gov/committee-activity/hearings/23-and-you-the-privacy-and-national-security-implications-of-the-23andme-bankruptcy.

[36] Ibid.

[37] AM Phillips, Buying Your Self on the Internet: Wrap Contracts and Personal Genomics (Edinburgh University Press 2019) pp182-7.

[38] M Sullivan, ‘23andMe has signed 12 other genetic data partnerships beyond Pfizer and Genentech’ (14 January 2015) VentureBeat https://venturebeat.com/2015/01/14/23andme-has-signed-12-other-genetic-data-partnerships-beyond-pfizer-and-genentech/ ; Christine Lagorio-Chafkin, ‘23andMe Exec: You Ain’t Seen Nothing Yet’ (7 January 2015) Inc http://www.inc.com/christine-lagorio/23andMe-newpartnerships.html.

[39] US Senate Committee on the Judiciary, ‘Grassley, Cornyn Introduce Bipartisan Bill to Safeguard Consumers’ Genetic Data After 23andMe Bankruptcy Sparks Privacy Concerns’ (27 May 2025). https://www.judiciary.senate.gov/press/rep/releases/grassley-cornyn-introduce-bipartisan-bill-to-safeguard-consumers-genetic-data-after-23andme-bankruptcy-sparks-privacy-concerns; and see S.1916 – Don’t Sell My DNA Act, S.1916 — 119th Congress (2025-2026) https://www.congress.gov/bill/119th-congress/senate-bill/1916/text/is.

[40] US Senate Committee on the Judiciary, ‘Grassley, Cornyn Introduce Bipartisan Bill to Safeguard Consumers’ Genetic Data After 23andMe Bankruptcy Sparks Privacy Concerns’ (27 May 2025) https://www.judiciary.senate.gov/press/rep/releases/grassley-cornyn-introduce-bipartisan-bill-to-safeguard-consumers-genetic-data-after-23andme-bankruptcy-sparks-privacy-concerns .

[41] Katrina Costa, ‘AI and the future of generative biology’ Sanger Science (17 October 2024) https://sangerinstitute.blog/2024/10/17/ai-and-the-future-of-generative-biology/ ; Jim Thomas, ‘Black Box Biotech’ Briefing Paper African Centre for Biodiversity (ACB), together with Third World Network (TWN) and ETC Group (September 2024) https://www.etcgroup.org/content/black-box-biotechnology; M Wang, et al, ‘A call for built-in biosecurity safeguards for generative AI tools’ (2025) Nat Biotechnol https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-025-02650-8.

[42] AM Phillips, Buying Your Self on the Internet: Wrap Contracts and Personal Genomics (Edinburgh University Press 2019); SI Becher and AM Phillips, ‘Data Rights and Consumer Contracts: The Case of Personal Genomic Services’ in D Clifford, KH Lau, JM Paterson (eds), Data Rights and Private Law (Hart Publishing, 14 December 2023). Earlier draft available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4180967; I jointly presented at PrivacyCon – AM Phillips and J Charbonneau, ‘Giving away more than your genome sequence?:Privacy in the Direct-to-Consumer Genetic Testing Space’ (https://www.ftc.gov/policy/public-comments/2015/10/09/comment-00057) American Federal Trade Commission’s PrivacyCon (January 2016).

[43] ICO, “23andMe fined £2.31 million for failing to protect UK users’ genetic data” (News, 17 June 2025) https://ico.org.uk/about-the-ico/media-centre/news-and-blogs/2025/06/23andme-fined-for-failing-to-protect-uk-users-genetic-data/; see also the ICO, Penalty Notice – 23andMe, Inc (5 June 2025) https://ico.org.uk/media2/kclbljpo/23andme-penalty-notice.pdf.

[44] ICO, “23andMe fined £2.31 million for failing to protect UK users’ genetic data”.

[45] Ibid; also see Privacy Laws & Business, “ICO fines DNA testing company 23andMe £2.31 Million”. http://xlpkz.mjt.lu/nl3/2sxB3-wx1hD9J_y4S4EAIQ?m=AV8AAHBbhp4AAc523IYAAR7sV1sAAYAyHtEAnRiUAA6KKgBoUY-i9J7fb3fNT-W-MuZPZ_dHEwAOYZc&b=bd2b381c&e=744bebfc&x=IQqvNdhRZblt2qg1LKXuRZ-FIUDAgEu6z6keowWxBJ8.

Comments